Between Worlds and Walls

A radical surrealist’s vision and an historic studio’s rebirth in St Ives.

Tate St Ives sits on the threshold of past and future, the weight of art history pressing against its white-walled galleries even as it gestures towards new horizons. Two major developments in 2025 reinforce this duality: a landmark exhibition on Ithell Colquhoun, the most esoteric of British surrealists, and the long-awaited restoration of the Palais de Danse, once the creative crucible of Barbara Hepworth. These twin stories are not mere coincidences but signals of a deeper resonance – a reminder that St Ives has always been a place where art, landscape and the intangible currents of the mystical and the modern converge.

For much of her life, Ithell Colquhoun stood at the fringes of British surrealism, a sorceress among painters, a painter among occultists. The upcoming exhibition, the largest ever staged of her work, pulls her from the margins and places her at the centre, unveiling a body of art that pulses with the strangeness of dream logic and the ancient symbols of forgotten rites.

With over 200 works on display, the exhibition is a passage through Colquhoun’s shifting identities: student of the Slade, surrealist provocateur, practitioner of automatic techniques, and ultimately, a seeker whose paintings became spellbooks of colour and form. Early pieces such as Judith Showing the Head of Holofernes (1929) reveal her fascination with the subversion of myth, reworking biblical narratives through an occultist lens. Nearby, her designs for The Bird of Hermes hint at a mind already alive to the coded languages of alchemy and transformation.

The centrepiece of the exhibition, however, lies in the works of the late 1930s and 1940s, when Colquhoun fully embraced Surrealism’s methods and possibilities. Scylla (méditerranée) (1938), a painting in which the female body dissolves into rock and water, exemplifies the double-image technique that so fascinated her. Elsewhere, Bonsoir (1939), an unmade surrealist film, is presented through an intricate storyboard, its sequences revealing an eye attuned to cinema’s capacity for dreamlike juxtaposition.

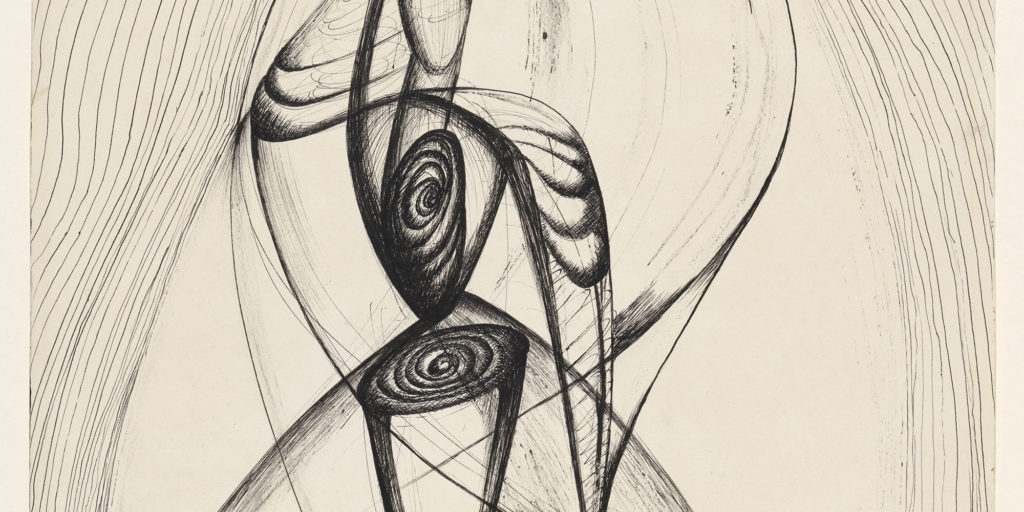

Yet Colquhoun was never content to remain within Surrealism’s confines. In the 1940s, she encountered the automatic techniques of Gordon Onslow Ford and Roberto Matta, leading to an artistic shift that embraced chance, fluidity and an unmediated connection to subconscious forces. The exhibition presents key works from this period, including Gorgon (1946) and Attributes of the Moon (1947), their swirling forms generated through decalcomania, a process in which paint is pressed between two surfaces to create spontaneous, otherworldly shapes. These are accompanied by their original transfer papers – relics of a process that sought to strip the artist’s hand from the act of creation.

By the late 1940s, Colquhoun’s practice had fused entirely with her esoteric pursuits. She immersed herself in alchemy, Kabbalah and Druidic traditions, seeking to encode her understanding of the universe into intricate compositions. Her Diagrams of Love series (1940–42) merges male and female forms in a kabbalistic union, while later works evoke landscapes as portals – thin places where the physical world brushes against the unseen.

Cornwall, with its standing stones and granite outcrops, became Colquhoun’s final sanctuary. She settled in Lamorna, a place whose prehistoric echoes found their way into her canvases. The exhibition’s final rooms bring together her visionary depictions of sacred sites, including Dance of the Nine Opals (1942), a work that transforms a stone circle into a whirling mandala of energy. The closing section presents her late experiments with enamel and her self-designed ‘Taro’ deck, distillations of a life spent navigating the spaces between art and magic.

As Colquhoun’s visions take shape within Tate St Ives, another kind of transformation is taking place just beyond its walls. The Palais de Danse, a landmark St Ives building closed to the public for 65 years, is set to be reborn. Thanks to a £2.8 million grant from The National Lottery Heritage Fund, the Palais will reopen as a cultural hub, reconnecting St Ives to a chapter of its artistic past that has remained hidden for decades.

Built in 1911 as St Ives’s first cinema, the Palais de Danse evolved into a dance hall before, in 1961, it became the second studio of Barbara Hepworth. It was here, amid its high ceilings and wooden floors, that she sculpted Single Form (1961–64), a monumental work commissioned for the United Nations. The Palais was more than just a workspace; it was a site of ambition, a space where Hepworth wrestled with the monumental, both in material and in vision.

The restoration project will return the building to public life, preserving its historic features while reimagining its purpose. The lower workshop, still marked by the grid Hepworth used to map out Single Form, will be restored as an immersive experience, allowing visitors to step into the sculptor’s world. Upstairs, the 24-metre dance hall will once again welcome movement – this time in the form of performances, screenings and community gatherings. Even the yard, long sealed off, will open to the public, offering a space for workshops and hands-on creativity.

Anne Barlow, Director of Tate St Ives, sees the project as both a tribute and a revival: “This brings us closer to realising our vision for the Palais as a living heritage site, one that honours Hepworth’s legacy while engaging directly with the people of St Ives.”

The significance of the Palais extends beyond its walls. It speaks to the broader story of St Ives, where art and life practice their dance together. Hepworth, like Colquhoun, was drawn to Cornwall’s elemental power, to the way light and land conspire to shape artistic imagination. That their legacies should intertwine once more in 2025 – Colquhoun’s retrospective unfolding as Hepworth’s studio reopens – feels not just fitting, but inevitable.

Tate St Ives has long been a guardian of artistic currents, attuned to the echoes of its surroundings. The Colquhoun exhibition and the Palais restoration are not simply acts of preservation or celebration; they are statements of intent. They affirm that art in St Ives is not a relic of the past, but a force that continues to shape and be shaped by this place.

Colquhoun saw Cornwall as a landscape alive with hidden energies. Hepworth saw it as a place where form could be honed and clarified. Between them, they encapsulate the two great impulses of St Ives art: the mystical and the material, the vision and the craft. As 2025 unfolds, their legacies will stand side by side once more, inviting us to step into their worlds and, perhaps, to see anew.